By Stephanie Barwick (@InSituSteph) and Victoria Brazil (@SocraticEM)

You’ve presented to ED with abdominal pain after surgery 2 weeks ago. You are in pain and hoping for answers. So far it has been a busy afternoon for you – a CT scan, doctors’ reviews, and nurses taking observations and giving you pain relief. Suddenly you hear an obnoxious, loud and frightening alarm, and witness your doctor and nurse exit your bay looking very apprehensive.

What would you be thinking? Would you be scared, concerned, worried?

What if I told you this wasn’t real, that it was our weekly in situ simulation – would your thoughts or feelings change? Would you be confused, excited, curious, annoyed? Would you want to be involved?

For readers of the ICE blog, in situ simulation (ISS) may be viewed as an effective way to train teams and evaluate the system in which we work. But how does it affect the patients and families who are being cared for?

These healthcare consumers (HCC) may be feeling anxiety, inconvenience, or perhaps thinking this the most exciting thing that has happened all day!

The integration of simulation into an active clinical environment creates a unique and interesting dynamic in which HCC are engaged – intentionally or unintentionally. A much-cited benefit of simulation is that it can be delivered without risk to patients (Blais, 2017; Pratt, 2012; Sweeney, Maietta, & Olson., 2015) – referring to the benefit of simulation moving away from ‘practising on patients’. However, this does not recognise the possibility of unintended harm – physical or psychological – with conducting simulation in an active clinical environment. There is limited awareness and management of safety risks to HCC during ISS.

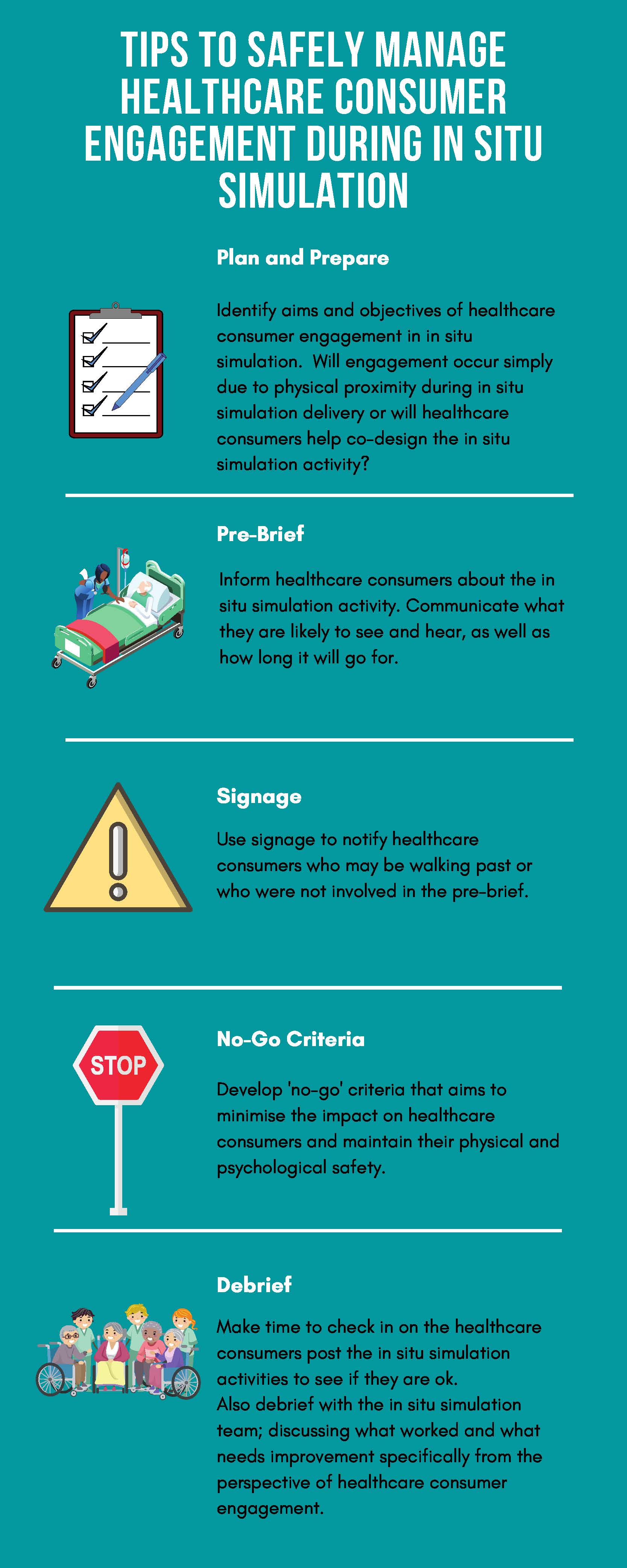

So how is this engagement safely managed? Part way through a major research program on this topic, we’d like to share 5 tips to safely manage HCC engagement during ISS.

Tip #1 – Plan and Prepare. Identify the aims and objectives of HCC engagement in ISS. HCC can contribute to design, delivery, and policy development in healthcare education (Towle et al. 2010), including simulation. This can help target patient focused outcomes, and help understand the potential physical or psychological risks.

Tip #2 – Implement effective communication strategies.

Pre-brief patients and families – share information about the nature and purpose of the simulation, what HCC will see and hear, and the duration of the simulation. (Yates, Webster, Jowsey and Weller, 2015; Hart, Thompson, Bourke, & Junk, 2016).

Eg. “We are about to conduct a simulation, which is where we run a medical scenario using a manikin. This provides an opportunity for our clinical teams to spend some time training together, it will take approximately 15mins, where you will hear some loud noises like alarms and see a large number of people responding to the simulated patient.”

Signage to notify bystanders that the activity is a simulation.

Tip #3 – Implement risk mitigation strategies. Develop a ‘no-go criteria’ for HCC engagement during delivery of ISS. These should consider current clinical activity and safety issues – taking into account workflow patterns, clinical load/acuity, and unanticipated events/threats to psychological safety (Bajaj, Minors, Walker, Meguerdichian, & Patterson, 2018). For example: if there has been a recent real-life medical emergency on the ward the ISS is planned for, consider the psychological impact this could have on the HCC who may be in physical proximity.

Tip #4 – Debrief – Identify and manage adverse outcomes. Spend time after the ISS activity talking to HCC in physical proximity to see if they are ok, and offer them the opportunity to debrief. Debriefing should also occur with the ISS team to reflect on what went well and what could be improved upon for HCC safety and engagement.

References

Bajaj, K., Minors, A., Walker, K., Meguerdichian, M., & Patterson, M. (2018). “No-Go Considerations” for In Situ Simulation Safety. Simul Healthc, 13(3), 221-224. doi:10.1097/sih.0000000000000301.

Blais, C. (2017). Using Nursing Simulation to Improve Early Recognition of Emergent Situations. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5454&context=dissertations.

Hart, C., Thompson, A., Bourke, T., & Junk, C. (2016). Parent opinion on multi-disciplinary in-situ simulation as paediatric emergencies training. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 101, A48. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2016-310863.80

Pratt, S. D. (2012). Simulation in obstetric anesthesia. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 114(1), 186-190.

Sweeney, J., Maietta, R., & Olson, K. (2015). An analysis comparing “Sim Huddles” to traditional simulation for obstetric emergency preparedness. Nursing for women’s health, 19(1), 16-25.

Towle, A., Bainbridge, L., Godolphin, W., Katz, A., Kline, C., Lown, B., . . . Thistlethwaite, J. (2010). Active patient involvement in the education of health professionals. Medical education, 44(1), 64-74.

Yates, K. M., Webster, C. S., Jowsey, T., & Weller, J. M. (2015). In situ simulation training in emergency departments: what patients really want to know. BMJ Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning, 1(1), 33-39. doi:10.1136/bmjstel-2014-000004.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. For more details on our site disclaimers, please see our ‘About’ page